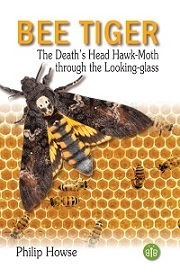

Bee Tiger: The Death’s Head Hawk-Moth through the Looking-glass

Philip Howse

Brambleby Books, £13.99

What a delightful book. As a passionate ant researcher, Bee Tiger is not something I would normally pick up, but I am so glad I was given the opportunity to read it. I am even left considering watching The Silence of the Lambs again to ensure I don’t miss the part played by the superstar of this book.

The Death’s Head Hawk-Moth (Archerontia atropis) is the largest moth seen in the British Isles. Found in Southern Europe, migrating to the northern regions, Africa and the Middle East, it has a bright yellow underwings and a body with black stripes resembling that of a bee. Remarkably, using sound and pheromones as well as looks, the moth can safely enter a honeybee nest and be accepted as one of the colony, making it a successful honey thief (hence the name “Bee Tiger”).

Philip Howse cleverly helps us to enter a world of amplified colours, shapes, sounds and odours as perceived by other organisms. The moth’s markings evolved to deceive its main predators, bats and birds, which both have dedicated chapters. In these, the author displays in-depth research into the thoughts of other scientists, writers, artists, poets and musicians on the overlap of the senses and synaesthesia. This digression leads us to consider whether bats hear in colour and how moths manage to outwit them through their own sounds, movements and unpleasant flavour if captured.

I have never considered looking at an insect from an angle other than above, but the author continues with poetic and historical stories about what it might be like in an insect world or to have different sensory perceptions. What would the features of the Death’s Head Hawk-Moth look like if you were face to face with it?

Howse has delved into a huge amount of literature on the distinctive skull-like markings of the Death’s Head Hawk-Moth, exploring myths, superstitions, witchcraft, the Medusa, Satan and symbols of death. It is fascinating to read of the moth appearing on gravestones, signifying that the buried body was infected with a disease to deter to grave robbers. It was even nailed on doors to keep evil spirits away. Yet the pupa, of the same species, was a symbol of regeneration. The Death’s Head Hawk-Moth is also known to be a pest, affecting honey production as an adult and attacking valuable crops as a caterpillar. The author leads us into further stories about the use of poisons, superstitions, Kings, famous painters and various publications; all of which have some association with the life cycle of the Death’s Head Hawk-Moth, its feeding habits or its means of survival.

Could the use of pesticides and other destructive human activites affect future populations of this attractive and colourful moth? Might this be the end of such wonderful legends, or will the moth continue to adapt and survive and find ways to overcome human activities and deceive us all? This is truly a remarkable book that makes us ponder not just a moth but a variety of historical events, concepts, rituals, beliefs and behaviours. I would encourage anyone, whatever their interests, to read this well written and unusual book.

Dr E J M Evesham